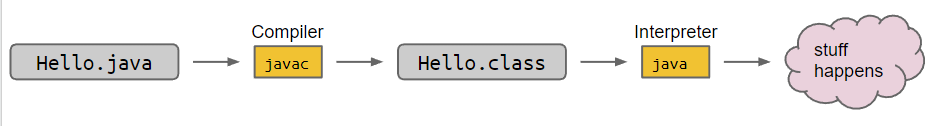

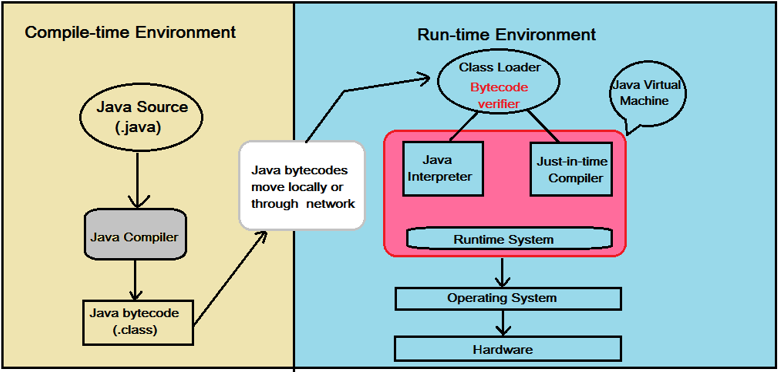

Compilation

Why make a class file at all?

- class file has been type checked. Distributed code is safer.

- class files are ‘simpler’ for machine to execute. Distributed code is faster.

- Minor benefit: Protects your intellectual property. No need to give out source.

$ ls

Main.java Triangle.java

$ javac Triangle.java

$ ls

Main.java Triangle.class Triangle.java

$ java Triangle.java

*

**

***

****

*****

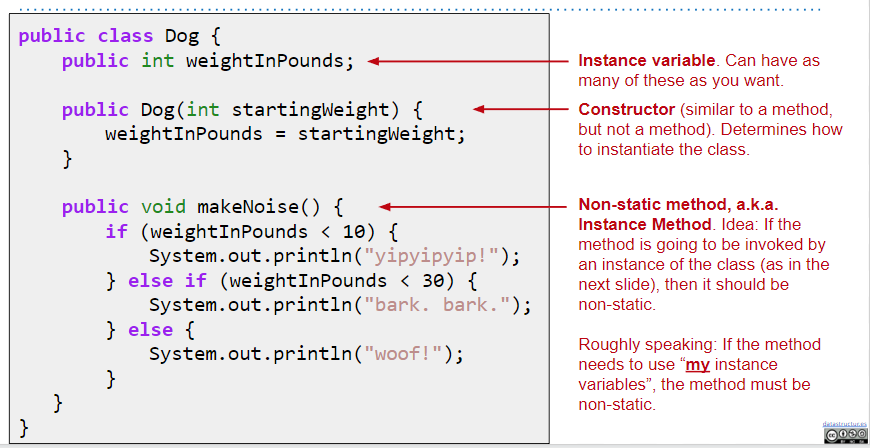

Defining and instantiating classes

The constructor public Dog(int startingWeight) in Java does the same thing as def __inti__(self) in Python.

Roughly speaking: If the method needs to use “my instance variables”, the method must be non-static. In other words, static methods can’t access “my” instance variables, because there is no “me”. Unless you get the variables through some instances, like:

public static Dog maxDog(Dog d1, Dog d2) {

if (d1.weightInPounds > d2.weightInPounds) {

return d1;

}

return d2;

}

You can access class attributes through instances, but it’s confusing and not recommended! Always access class attributes through class names and access instance attributes through instances.

In the non-statics methods, you can use keyword this which is the same as self in Python.

public Dog maxDog(Dog d2){

if (this.weightInPounds > d2.weightInPounds) {

return this;

}else {

return d2;

}

}

References

Class instantiations

When we instantiate an object:

- Java first allocates a box of bits for each instance variables of the class and fills them with a default value

- The constructor then usually fills every such box with some other value

Reference types

There are 8 primitive types in Java: byte, short, int, long, float, double, boolean, char.

Everything else, including arrays, is a reference type.

Reference type variable declarations

When we declare a variable of any reference type:

- Java allocates exactly a box of size 64 bits, no matter what type of object.

- These bits can be either set to:

- Null(all zeros)

- The 64 bit “address” of a specific instance of that class(returned by

new)

As for arrays:

- Creates a 64 bit box for storing an int array address. (declaration)

- Creates a new Object, in this case an int array. (instantiation)

- Puts the address of this new Object into the 64 bit box named

a. (assignment)

The golden rule of equals(GRoE)

Given variables y and x, y = x copies all the bits from x into y, no matter primitive types or reference types. If it’s reference type, in terms of our visual metaphor, we “copy” the arrow by making the arrow in the y box point at the same instance as x.

Passing parameters obeys the same rule: Simply copy the bits to the new scope.

In the example, below, after switcheroo, foobar.x:10 foobar.y: 20 baz.x: 30 baz.y: 40.

public class Foo {

public int x, y;

public Foo (int x, int y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public static void switcheroo (Foo a, Foo b) {

Foo temp = a;

a = b;

b = temp;

}

public static void main (String[] args) {

Foo foobar = new Foo(10, 20);

Foo baz = new Foo(30, 40);

switcheroo(foobar, baz);

}

}

Class object

static variables/methods VS instance variables/methods

In the code below, title, library are instance variables and Book, getTitle are instance methods, which can not be accessed by class name or static methods. last is static variable and lastBookTitle is static method, which can be accessed by instance or class name.

class Book {

public String title;

public Library library;

public static Book last = null;

public Book(String name) {

title = name;

last = this;

library = null;

}

public static String lastBookTitle() {

return last.title;

}

public String getTitle() {

return title;

}

}

Generics

Java allows us to defer type selection until declaration.

public class SLList<BleepBlorp> {

private IntNode sentinel;

private int size;

public class IntNode {

public BleepBlorp item;

public IntNode next;

...

}

...

}

SLList<Integer> s1 = new SLList<>(5);

s1.insertFront(10);

SLList<String> s2 = new SLList<>("hi");

s2.insertFront("apple");

- In the .java file implementing your data structure, specify your “generic type” only once at the very top of the file.

- In .java files that use your data structure, specify desired type once:

- Write out desired type during declaration.

- Use the empty diamond operator <> during instantiation.

- When declaring or instantiating your data structure, use the reference type.

- int: Integer

- double: Double

- char: Character

- boolean: Boolean

- long: Long

```java

DLList

s1 = new DLList<>(5.3);

double x = 9.3 + 15.2; s1.insertFront(x);

## Inheritance

### Golden rules(summary)

1. Compiler allows memory box to hold any subtype.

2. Compiler allows calls based on static type.

* so when we pass a variable as an argument to a method, we need to check if the **static type** of the argument is compatible to the parameter type

* so when we call a method through an instance, we need to find if there is such a method in the static type class of the instance(or its superclass). If there is one, then we can further check if there is an overriden version of this method in the dynamic type class.

3. Overridden **non-static** methods are selected at **run time** based on **dynamic type**. **Everything else is based on static type**, including overloaded methods.

4. You can do casting `(SpecificType) variableWithGerneralStaticType`, it may not raise any compile error, but it definitely will raise a **runtime error**, because it's illegal to say "a variable with general static type is-a specific type", in other words, a memory box cannot hold its parent type.

### Overriding VS overloading

If a “subclass” has a method with the **exact same signature** as in the “superclass”, we say the subclass overrides the method. (An overriding method can also return a subtype of the type returned by the overridden method. This subtype is called a covariant return type.)

Methods with the **same name but different signatures** are overloaded.

<figure align="center">

<img src = "/assets/images/computer%20science/overide_1.png">

<figcaption>figure from <a href="https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1EUOpd9NXq28eEUqQMZoo_rRpxw8EekQ2LEp61U9bnDc/edit#slide=id.g109ce79706_0_414">CS61B</a>

</figcaption>

</figure>

If you mark an overriding method with the `@Override` annotation, then the code won’t compile if it is not actually an overriding method. Even if you don’t write `@Override`, subclass still overrides the method. `@Override` is just an optional reminder that you’re overriding.

<figure align="center">

<img src = "/assets/images/computer%20science/override_2.png">

<figcaption>figure from <a href="https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1EUOpd9NXq28eEUqQMZoo_rRpxw8EekQ2LEp61U9bnDc/edit#slide=id.g109ce79706_0_414">CS61B</a>

</figcaption>

</figure>

### Overriding VS Hiding

First of all, it's a bad programming habit to write hiding variables or methods in subclasses. It's confusing, please avoid it.

**Overriding**: Overriding in Java simply means that the particular method would be called based on the **run time type** of the object and **not** on the compile time type of it (which is the case with overriden static methods).

**Hiding**: **Parent class methods that are static are not part of a child class (although they are accessible), so there is no question of overriding it**. Even if you add another static method in a subclass, identical to the one in its parent class, this subclass static method is unique and distinct from the static method in its parent class. If a subclass has variable with the same name as a superclass, it's also hiding.

<figure align="center">

<img src = "/assets/images/computer%20science/dynamic_type_2.png">

<figcaption>figure from <a href="https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/IandI/override.html">Overriding and Hiding Methods</a>

</figcaption>

</figure>

### Static Type vs. Dynamic Type

Every variable in Java has a “**compile-time type**”, a.k.a. “**static type**”.

This is the type specified at declaration. Never changes!

Variables also have a “**run-time type**”, a.k.a. “**dynamic type**”.

This is the type specified at instantiation (e.g. when using new).

Equal to the type of the object being pointed at.

<figure align="center">

<img src = "/assets/images/computer%20science/dynamic_type.png">

<figcaption>figure from <a href="https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1EUOpd9NXq28eEUqQMZoo_rRpxw8EekQ2LEp61U9bnDc/edit#slide=id.g1c5d63f7bc_0_316">CS61B</a>

</figcaption>

</figure>

* If **overridden**, decide which method to call based on run-time type(dynamic type) of variable.

* Compiler allows **method calls** based on compile-time type(static type) of variable. Compiler also allows **assignments** based on compile-time types(static type).

<figure align="center">

<img src = "/assets/images/computer%20science/dynamic_type——1.png">

<figcaption>figure from <a href="https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1zsr4-MHM5STYr_b0l-lZ8ABqAPzyIU3P31qWKP2M3m4/edit#slide=id.g10a4194b67_0_462">CS61B</a>

</figcaption>

</figure>

#### Casting

Java has a special syntax for specifying the compile-time type of any expression.

It's handy but also dangerous. The code below will raise ClassCastException because the result of maxDog(frank, frankSr) here is Frank Sr. which is a Malamute, which can not be cast as a Poodle.

```java

Poodle frank = new Poodle("Frank", 5);

Malamute frankSr = new Malamute("Frank Sr.", 100);

Poodle largerPoodle = (Poodle) maxDog(frank, frankSr);

Interface Inhheritance

Keyword: interface, implements

interface is a specification of what a List is able to do, not how to do it. Notice, private variables/methods are not allowed to be here, they are about “how to do”.

implements provides the body of the interface method.

public interface List61B<Item> {

public void insert(Item x, int position);

public void addFirst(Item x);

public void addLast(Item x);

public Item getFirst();

public Item getLast();

public Item get(int i);

public int size();

public Item removeLast();

default public void print() {

for (int i = 0; i < size(); i += 1) {

System.out.print(get(i) + " ");

}

}

}

Implementation Inheritance

-

Interface inheritance: Subclass inherits signatures, but NOT implementation.

-

implementation inheritance: Subclasses can inherit signatures AND implementation.

Keyword: default

Use the default keyword to specify a method that subclasses should inherit from an interface. Without the default keyword, methods in interface class can’t have a body.

public interface List61B<Item> {

public void addFirst(Item x);

public void addLast(Item y);

public Item getFirst();

public Item getLast();

public Item removeLast();

public Item get(int i);

public void insert(Item x, int position);

public int size();

default public void print() {

for (int i = 0; i < size(); i += 1) {

System.out.print(get(i) + " ");

}

System.out.println();

}

}

keyword: extends

When a class is a hyponym of an interface, we used implements.

Example: SLList<Blorp> implements List61B<Blorp>

If you want one class to be a hyponym of another class, you use extends. Example: VengefulSLList<Blorp> extends SLList<Blorp>.

Because of extends, RotatingSLList inherits all members of SLList:

- All instance and static variables.

- All methods.

- All nested classes.

Constructors are not inherited.

But if every VengefulSLList is-an SLList, every VengefulSLList must be set up like an SLList. If you didn’t call SLList constructor, sentinel would be null. Very bad.

- You can explicitly call the constructor with the keyword

super(no dot). - If you don’t explicitly call the constructor, Java will automatically do it for you.

Constructor A and constructor B below are exactly the equivalent.

//constructor A

public VengefulSLList() {

deletedItems = new SLList<Item>();

}

//constructor B

public VengefulSLList() {

super();

deletedItems = new SLList<Item>();

}

If you want to use a super constructor other than the no-argument constructor, can give parameters to super. If you don’t do super(x) by yourself, Java will call the default super() for you which probably not what you want.

public VengefulSLList(Item x) {

super(x);

deletedItems = new SLList<Item>();

}

Except constructor, another situation to use keyword super: use superclass’s methods when overriding, example:

@Override

public Item removeLast() {

Item oldBack = super.removeLast();

deletedItems.addLast(oldBack);

return oldBack;

}

extends vs implements

How do you know whether to use implements or extends?

- You must use “implements” if the hypernym is an interface and the hyponym is a class (e.g. hypernym List, hyponym AList).

- You must use “extends” in all other cases.

There’s no choice that you have to make, the Java designers just picked a different keyword for the two cases.

Arrays

Three valid notations:

- x = new int[3];

- y = new int[]{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

- int[] z = {9, 10, 11, 12, 13};

Especially, int[0] means empty array.

copy

Two ways to copy arrays:

- Item by item using a loop.

- Using

arraycopy.System.arraycopy(b, 0, x, 3, 2). Takes 5 parameters:- Source array

- Start position in source

- Target array

- Start position in target

- Number to copy

arraycopy is (likely to be) faster, particularly for large arrays.

2D arrays

int[][] matrix;

matrix = new int[4][]; //Creates 1 total array.

matrix = new int[4][4]; //Creates 5 total arrays.

generics

Instead of new Item[100], it’s (Item[]) new Object[100].

public class AList<Item> {

private Item[] items;

private int size;

/** Creates an empty list. */

public AList() {

items = (Item[]) new Object[100];

size = 0;

}

/** Resizes the underlying array to the target capacity. */

private void resize(int capacity) {

Item[] a = (Item[]) new Object[capacity];

System.arraycopy(items, 0, a, 0, size);

items = a;

}

/** Inserts X into the back of the list. */

public void addLast(Item x) {

if (size == items.length) {

resize(size + 1);

}

items[size] = x;

size = size + 1;

}

High order functions

Old School (Java 7 and earlier)

Fundamental issue: Memory boxes (variables) cannot contain pointers to functions. You cannot take a function as argument because a function doesn’t have a type and Java needs to do type checking for functions.

Solution: higher order functions using interfaces in Java.

If we want to implement a function do_twice which takes a function TenX as argument, we first write an interface IntUnaryFunction with apply method, then implement it by TenX overriding apply, finally instantiate class TenX and take this variable as argument for high order function do_twice. Code as below:

public interface IntUnaryFunction {

int apply(int x);

}

public class TenX implements IntUnaryFunction {

public int apply(int x) {

return 10 * x;

}

}

public class HoFDemo {

public static int do_twice(IntUnaryFunction f, int x) {

return f.apply(f.apply(x));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(do_twice(new TenX(), 2));

}

}

Java 8 or Later

In Java 8, new type Function was introduced: now we can hold references to methods. However, the old way is still widely used.

Example:

public class Java8HoFDemo {

public static int tenX(int x) {

return 10*x;

}

public static int doTwice(Function<Integer, Integer> f, int x) {

return f.apply(f.apply(x));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

int result = doTwice(Java8HoFDemo::tenX, 2);

System.out.println(result);

}

}

this, ==, equals

this

You can use this to access your own instance variables or methods.

- Unlike Python, where

selfis mandatory, usingthisin Java is not mandatory. - If there’s ever a name conflict where a local variable(methods) has the same name as an instance variable(methods), you must use

thisif you want to access the instance variable(methods).

Example:

public Dog(int size){

this.size = size;

}

== VS equals

== and .equals() behave differently

- == compares the bits. For references, == means “referencing the same object.”

- To test equality in the sense we usually mean it, use

.equalsfor class- but it requires writing a (overriden)

.equalsmethod for your classes, because the default implementation(in superclassObject) uses==(probably not what you want)

- but it requires writing a (overriden)

Example:

@Override

public boolean equals(Object o){

if (o instanceof Arrayset oas){

if (this.size != oas.size){

return false;

}

for (T x: this){

if (!oas.contain(x)){

return false;

}

}

}

return false;

}

Keyword: instanceof

In the code just above, we see how to use instanceof.

What does it do?

- checks to see if oas’s dynamic type is

Arraysetor its subtypes. - cast

oto a variable of static typeArraysetcalledoas.

It will work correctly even if o is null.