You might have heard many different data stuctures like arrays, linked lists, trees, queues and tries. Actually, they are not that different. Some of them are variations of basic data structures – Arrays, Linked Lists, Hash Tables and Tries – that will be mentioned in this article.

One golden rule of learning anything, start from the basics, and then follow you interest to explore more.

So let’s get started!

Summary

To get a big picture of what we will learn, first take a look at the comparison table of four basic data structures which will be explained in detail later.

| Data Structures | Descriptions | Pros | Cons | Time complexity for searching | Time complexity for insertion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrays | store fixed-number of variables with the same data types in continuous memory | 1. Lookup is gread. Random access, constant time 2.Easy to sort. That’s why sorting algrithms are executed with arrays. |

1. Insertion is bad. Lots of shifting to fit an element in the middle. 2.Deletion is bad. Lots of shifting after removing an element 3.Fixed size means less flexibility. |

O(1) | O(n) |

| Linked lists | nodes chained by pointers in one or two directions | 1. Doubly-linked lists are good at deletion of a given node> |

1. bad at searching 2.Doubly-linked lists take up more memory |

O(n) | O(n), to maintain sorted; O(1), no need to maintain sorted |

| Hash tables | the combination of array and linked list | 1. Insertion can start to tend toward$\Theta(1)$. 2.Deletion can start to tend toward$\Theta(1)$. 3. Lookup can start to tend toward $\Theta(1)$ |

1. Bad at sorting 2. performs bad when collission occurs too frequently. |

O(n) | $\Theta(1)$ |

| Tries | tree whose nodes are pointer arrays | 1. good at Insertion, deletion, and searching | 1. takes up more memory | O(1) | O(1) |

Arrays

As we mentioned in the first section, arrays have fixed sizes, which makes it difficult to insert or delete elements.

For example, if we want to add one more element at the end of the array(which is already the simpliest insertion case), we need one more chunk of space just after the current last element’s memory. However, nobody knows if there is enough empty space for us. If there is, we can just take up this memory; If there isn’t, we need to find another continous memory that can store all our elements, copy values in the old arrays to the new arrays, and then free the old arrays’ memory. Although you can use realloc()function to do this for you, the process under the hood is the same inefficient.

Given that arrays are bad at insertion and deletion, we need new data structure to do these jobs.

Linked lists

Different from arrays that have fixed size, linked lists are designed to store a collection of elements with flexibility in size. We can expand or shrink the memory of linked lists easily without waste.

There are two kinds of linked lists, Singly-linked Lists moving only in one direction through the list, and Doubly-linked Lists moving forward and backward through the list. It’s he design of node that makes them different.

Comparison of singly-linked lists and doubly-linked lists:

| Singly-linked lists | Doubly-linked lists | |

|---|---|---|

| node | one pointer pointing to the next node | two pointers, one pointing to the next node, one pointing to the previous node |

| direction | traversal in one direction only | traversal possible in two directions |

| memory | less | more |

| complexity of insertion and deletion at a given position | O(n) | O(n/2)=O(n) |

| complexity of deletion with a given node | O(n), because the previous node needs to be known, and traversal takes O(n) | O(1),because the design of node makes it easy to know the previous node |

| variations | execution of stacks | execution of heeps, stacks and binary trees |

Singly-linked lists

Nodes

Linked lists are composed of units we called nodes. A linked list node is a special kind of struct with two filed:

- data of some data type

- a pointer to another node of the same type.

Implement a node with one integer field and one pointer field pointing to a node by struct:

typedef struct node

{

int number;

struct node *next;

}

node;

Actually, arrays can also store elements which are defined struct. What makes linked list special? The answer is the pointer field recording the address of the element itself in the struct. Due to this design, elements don’t have to be stored in continuous memory like in arrays. That’s why this data structure is more flexible.

The pointer of the last node in a linked list is NULL because there is no next node that it needs to point to.

Implement a linked list

We will implement a linked list using the struct we just defined.

- This linked list will start from no element in it.

- Then, we can create the first node for the linked list and makes it points to a chunk of memory that can stores a node type variable.

- Always check if your pointer is NULL after asking for dynamically-allocated memory.

- Let’s initialize this node by assigning 1 to the number field and NULL to the pointer field(because this is the first node in the linked list but also the last node).

- Add the node to the linked list. What we actually do is to make

llistpoints to the box pointed to by the node we createdn. - Let’s add one more node to the linked list to make it more realistic. Ask for another space of dynamically-allocated memory and initialize the node. Basically, repeat step 2, step 3 and step 4.

- Similar to step 5, we want to add this new node to linked list. But it’s a bit different. Instead of making linked list pointing to the node, we let the first node(which is exactly the node pointed to by

llist) points to the address of the new node. Now, the linked list is a chain of nodes linked together. - Use our linked list, like printing values of elements in it.

- At the end, we need to

freeall our dynamically-allocated memory from the first node to the last node.

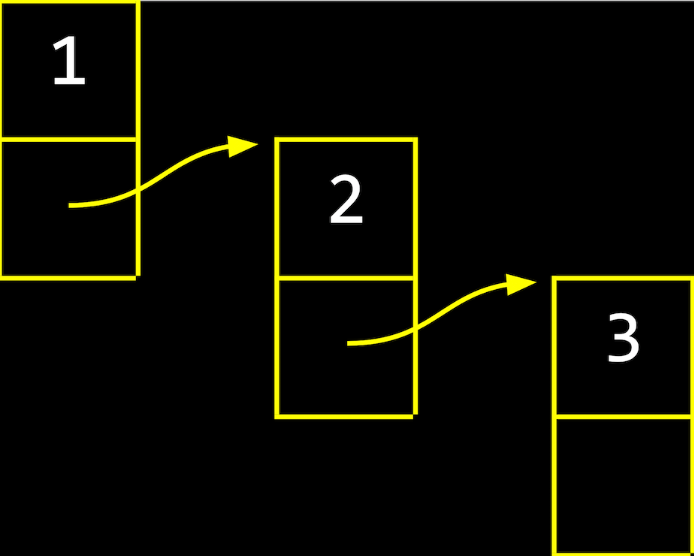

The code below also shows us how to insert a node between the first node and the second node:

int main(void) {

node* llist = NULL;

node* n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

n->number = 1;

n->next = NULL;

}

else{

return 1;

}

llist = n;

n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

n->number = 2;

n->next = NULL;

}

else{

free(llist);

return 1;

}

llist->next = n;

n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

n->number = 3;

n->next = llist->next;

}

else{

free(llist);

free(llist->next);

}

llist->next = n;

for (node* tmp = llist; tmp != NULL; tmp = tmp->next)

{

printf("%d\n", tmp->number);

}

while (llist != NULL)

{

node* tmp = llist->next;

free(llist);

llist = tmp;

}

}

The code releasing the memory of linked lists is kind of tricky(but on the positive side, it practices your visualization of how linked list is chained), recursion is a better choice:

void destroy(node* head)

{

if (head == NULL)

{

printf("NULL");

return;

}

else{

destroy(head->next);

printf("%d is freed", head->number);

free(head);

}

}

Doubly-linked lists

Nodes

Nodes in doubly-linked lists have two pointer fields, one pointing to the last element, and one pointing to the next element. It makes deletion with a given node simpler, but spends more memory space. It’s a trade-off you need to make.

typedef struct node_tag{

int number;

node_tag* previous;

node_tag* next;

}node;

Both the previous pointer of the first node and the next pointer of the last node in a doubly-linked list are NULL.

Implement a linked list

node* llist = NULL;

// add one node to linked list

node* n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

n->number = 1;

n->previous = NULL;

n->next = NULL;

}

else{

return 1;

}

llist = n;

//add another node to the linked list

n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

n->number = 2;

n->previous = llist;

n->next = NULL;

}

else{

free(llist);

return 1;

}

// insert an node between the current two nodes

llist->next = n;

n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

n->number = 3;

n->previous = llist;

n->next = llist->next;

}

else{

free(llist);

free(llist->next);

}

llist->next = n;

n->next->previous = n;

//delete a given node

delete(llist, n);

for (node* tmp = llist; tmp != NULL; tmp = tmp->next)

{

printf("%d\n", tmp->number);

}

destroy(llist);

delete a given node:

void delete(node* head, node* target)

{

if (head == NULL || target == NULL)

{

return;

}

//when the head needs to be moved

if (target == head)

{

head = target->next;

}

//when target is not the first node

if (target->previous != NULL)

{

target->previous->next = target->next;

}

//when target is not the last node

if (target->next != NULL)

{

target->next->previous = target->previous;

}

free(target);

}

Hash tables

Hash tables, a creative data structure, combine the random access ability of arrays and dynamics of linked lists. The idea is that we run our data through the hash function, and then store the data in the element of the array represented by the returned hash code.

The tradeoff is that hash tables are not good at sorting.

Hash functions

Hash function maps data(like a text or lists of numbers) to an integer value being used as the index of this element in the hash table. This process is called hashing. So when we want to find the location of an element(a key), we can use hash function to get an index(a value) of the array. A good hash function should:

- use only the data being hashed

- use all the data being hashed

- be deterministic, which means every time we pass the same data into the hash function, we get the same hash code out.

- uniformly distribute data(spread in the range)

- generate very different values for very similar input data(?)

Here we have a hash function example, however, it’s waste of time to write your own hash functions, because there is already a bunch of them available on the internet and yours probably are not good as them.

unsigned int hash(char* str)

{

int sum = 0;

for (int i = 0; str[i] != '\0\; i++)

{

sum += str[i];

}

retrun sum % HASH_MAX;

}

Notice, it’s possible that two different data put into the hash function, and get the same return. We call it as collision. But this won’t be a problem because hash table is not a regular array, it also takes the advantage of linked lists, remember?

Chaining

In hash table, each element of the array is a pointer to the head of a linked list where we store data with the same return from hash function. It’s like cutting a long linked list into many small linked lists that are indexed in an array.

Example:

typedef struct node

{

char word[LONGEST_WORD + 1];

struct node *next;

}node;

node* hashtable[10];//declare a hash table

int x = hash("May");//get the index of "May" by hash function, assume we get a return 3;

node* n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

strcpy(n->word, "May");

n->next = NULL;

}

hashtable[x] = n;

x = hash("June");//assume "June" is also mapped to 3;

n = malloc(sizeof(node));

if (n != NULL)

{

strcpy(n->word, "June");

n->next = hashtable[x];

}

hashtable[x] = n;//the new node added will be the new head

Tries

Trie is short for retrieval.

The data to be searched for in a trie is a roadmap.

- if you can follow the map from beiginning to end, the data exists in the trie

- if not, it doesn’t Trie is a tree whose root and leaves nodes are arrays of pointers.

Example:

typedef struct node

{

bool is_word;

struct node *children[SIZE_OF_ALPHABET];

}node;