This article includes notes of CS61A lectures from week4 to week 6.

Recursion

Definition: A function is called recursive if the body of that function calls itself, either directly or indirectly

Implication: Executing the body of a recursive function may require applying that function

Example: call the function as many times as you want

We define a function print_num which prints the input number and return itself. The magic of this self-called function is that you can call it as many times as you want,

def print_num(x):

print(x)

return print_num

print_num(1)(2)(5)

print_num(2)

print_num(4)(3)

Iterations and recursions

When you convert iteration to recursion, you can pass the state of the iteration as arguments.

def sum_digits(n):

"""Return the sum of the digits of positive integer n."""

if n < 10:

return n

else:

all_but_last, last = split(n)

return sum_digits(all_but_last) + last`

# convert recursion to iteration

def sum_digits_iter(n):

digit_sum = 0

while n > 0:

n, last = split(n)

digit_sum = digit_sum + last

return digit_sum

# convert iteration to recursion

def sum_digits_rec(n, digit_sum):

if n > 0:

n, last = split(n)

return sum_digits_rec(n, digit_sum + last)

else:

return digit_sum

Example: Inverse Cascade

In order to understand the execution order of recursion cases, take a look at this example:

def inverse_cascade(n):

grow(n)

print(n)

shrink(n)

def f_then_g(f, g, n):

if n:

f(n)

g(n)

grow = lambda n: f_then_g(grow, print, n//10)

shrink = lambda n: f_then_g(print, shrink, n//10)

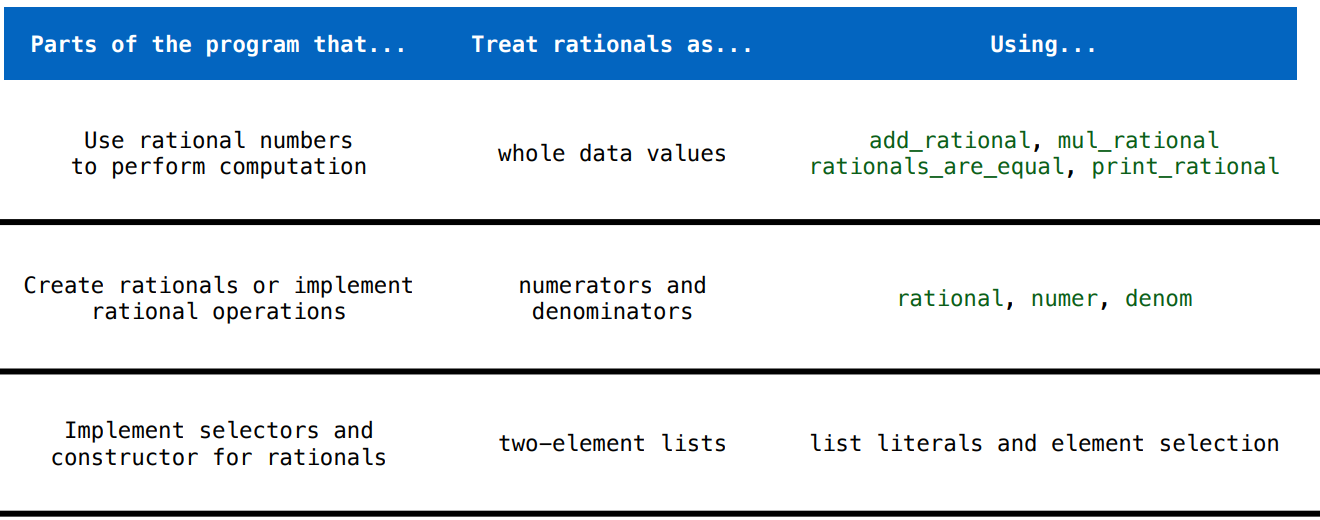

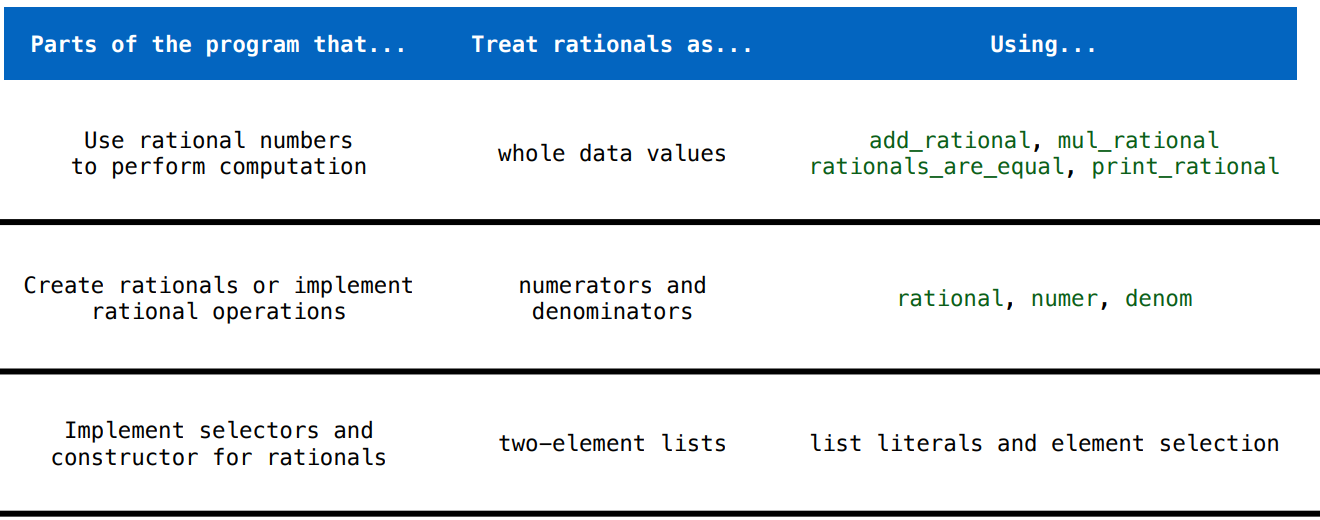

Data abstraction

Constructors and selectors

When we’re solving problems, the objects we’re facing might be compound data, for example, real numbers(composed of numerator and denominator). We should:

- Use constructors and selectors to represent data

- Use the representation to implement relevant operations or perform computations

The advantages of data abstraction is that if you change your representation, it doesn’t impact the use of implementations.

To be a great programmer, don’t break abstraction barriers. It makes your program more clear and easy to change in the future.

What are barriers in abstraction? The real numer example:

How to check whether the representation is valid? We can use math definition or rules defined by problems to build behavior condition. If the behavior condition is met, then the representation is valid. For example, if we construct rational number x from numerator n and denominator d, then numer(x) / denom(x) must equal n/d.

from math import gcd

#constructor

def rational(n, d):

"""Construct a rational number that represents N/D."""

g = gcd(n, d)

return [n//g, d//g]

# selectors

def numer(x):

"""Return the numerator of rational number X."""

return x[0]

def denom(x):

"""Return the denominator of rational number X."""

return x[1]

# implementation

def mul_rational(x, y):

return rational(numer(x) * numer(y), denom(x) * denom(y))

def add_rational(x, y):

nx, dx = numer(x), denom(x)

ny, dy = numer(y), denom(y)

return rational(nx * dy + ny * dx, dx * dy)

def print_rational(x):

print(numer(x), '/', denom(x))

def rationals_are_equal(x, y):

return numer(x) * denom(y) == numer(y) * denom(x)

Trees

Recursive description (wooden trees):

- A tree has a root label and a list of branches

- Each branch is a tree

- A tree with zero branches is called a leaf

- A tree starts at the root

Relative description (family trees):

- Each location in a tree is called a node

- Each node has a label that can be any value

- One node can be the parent/child of another

- The top node is the root node

Tree ADT:

Constructor and selector

def tree(label, branches=[]):

"""Construct a tree with the given label value and a list of branches."""

for branch in branches:

assert is_tree(branch), 'branches must be trees'

return [label] + list(branches)

def label(tree):

"""Return the label value of a tree."""

return tree[0]

def branches(tree):

"""Return the list of branches of the given tree."""

return tree[1:]

def is_tree(tree):

"""Returns True if the given tree is a tree, and False otherwise."""

if type(tree) != list or len(tree) < 1:

return False

for branch in branches(tree):

if not is_tree(branch):

return False

return True

def is_leaf(tree):

"""Returns True if the given tree's list of branches is empty, and False

otherwise.

"""

return not branches(tree)

def print_tree(t, indent=0):

"""Print a representation of this tree in which each node is

indented by two spaces times its depth from the root.

"""

print(' ' * indent + str(label(t)))

for b in branches(t):

print_tree(b, indent + 1)

Class

class Tree:

"""

>>> t = Tree(3, [Tree(2, [Tree(5)]), Tree(4)])

>>> t.label

3

>>> t.branches[0].label

2

>>> t.branches[1].is_leaf()

True

"""

def __init__(self, label, branches=[]):

for b in branches:

assert isinstance(b, Tree)

self.label = label

self.branches = list(branches)

def is_leaf(self):

return not self.branches

def __repr__(self):

if self.branches:

branch_str = ', ' + repr(self.branches)

else:

branch_str = ''

return 'Tree({0}{1})'.format(self.label, branch_str)

def __str__(self):

def print_tree(t, indent=0):

tree_str = ' ' * indent + str(t.label) + "\n"

for b in t.branches:

tree_str += print_tree(b, indent + 1)

return tree_str

return print_tree(self).rstrip()

Objects

What is Object?

Objects represent information. They consist of data and behavior, bundled together to create abstractions. Objects can represent things, but also properties, interactions, & processes

A type of object is called a class; classes are first-class values in Python.

Actually, all the values(‘int, 'float, etc.) and functions are objects in python.

Python is Object-oriented programming, which means in python object is:

- A metaphor for organizing large programs

- Special syntax that can improve the composition of programs

```python

int

<class ‘int’>

def foo(): pass foo.call

<method-wrapper ‘call’ of function object at 0x000002641DD1F040>

## Mutation

Object can change its value over time.

* **Mutation** is used to describe changes to objects

* **Mutability** describes the ability to change Python objects.

* A mutable object can be changed but an immutable object cannot. **Lists and dictionaries are mutable objects, while tuples are immutable objects.** So, tuple can be used as keys in dictionary, list cannot. When you use list as key in dictionary, it will raise `unhashable error`.

* An immutable sequence may still change if it contains a mutable value as an element.

**Mutable Default Arguments are Dangerous. A default argument value is part of a function value, and this argument is bound to the same value every time the function is called.** If the default value is mutable and the function mutates it, then each time the function is called, this default value will be changed subsequently.

Mutable function(function with default mutable arguments) is non-pure function, because it has side effect -- the default argument is mutated -- when it's called.

```python

>>> def f(s=[]):

... s.append(3)

... return len(s)

...

>>> f()

1

>>> f()

2

>>> f()

3

The difference between identity and equality

>>> x = 2

>>> y = 2

>>> x is y

True

>>> x=[10]

>>> y=[10]

>>> x is y

False

>>> x == y

True

>>> a, b = lst, lst[:]

>>> a is lst

True

>>> b is lst

False

Iterators

A container can provide an iterator that provides access to its elements in order

iter(iterable): Return an iterator over the elements of an iterable value

next(iterator): Return the next element in an iterator

- All iterators are mutable

- A dictionary, its keys, its values, and its items are all iterable values

If we use an iterator in a for statement, we can still go through the iterator until we reach the end. But that would end the iterator, so we can’t use it again. While if we use an iterable object like range(), every time we use it in a for statement, we can go through the content from beginning to end.

>>> s = [1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> t = iter(s)

>>> next(t)

1

>>> next(t)

2

>>> next(iter(s))

1

>>> next(iter(t))

3

>>> next(iter(s))

1

>>> next(iter(t))

4

>>> next(iter(t))

StopIteration

>>> map_iter = map(lambda x : x + 10, range(5))

>>> next(map_iter)

10

>>> next(map_iter)

11

>>> list(map_iter)

[12,13,14]

Generators

- A generator function is a function that yields values instead of returning them

- A generator is an iterator created automatically by calling a generator function

- When a generator function is called, it returns a generator that iterates over its yields

>>> def plus_minus(x):

... yield x

... yield -x

>>> t = plus_minus(3)

>>> next(t)

3

>>> next(t)

-3

>>> t

A

yield fromstatement yields all values from an iterator or iterable (Python 3.3)

def a_then_b(a, b):

yield from a

yield from b

list(a_then_b([3, 4], [5, 6])) # display [3, 4, 5, 6]

Classes

A class is a type (or category) of objects.

Attributes

All objects have attributes, which are name-value pairs.

Classes are objects too, so they have attributes. It has two types of attributes:

- Instance attribute: attribute of an instance

- Class attribute: attribute of the class of an instance

To evaluate a dot expression:

- Evaluate the

to the left of the dot, which yields the object of the dot expression -

is matched against the instance attributes of that object; if an attribute with that name exists, its value is returned - **If not,

is looked up in the class, which yields a class attribute value.** Class attributes are "shared" across all instances of a class because they are attributes of the class, not the instance - If this is subclass inherited from a base class, look up the name in the base class, if there is one.

- but it’s different from assignment. If interest is a class attribute, but we assign value to tom_instance.interest, then an instance attribute interest will be created for this instance.

-

That value is returned unless it is a function, in which case a bound method is returned instead ```python class Account: interest = 0.02 # A class attribute,it’s part of the class!

def init(self, account_holder): self.balance = 0 self.holder = account_holder # Additional methods would be defined here

tom_account = Account(‘Tom’) jim_account = Account(‘Jim’) tom_account.interest 0.02 jim_account.interest 0.02 ``` Attributes assignment example:

Using getattr, we can look up an attribute using a string, getattr and dot expressions look up a name in the same way.

>>> tom_account.balance

10

>>> getattr(tom_account, 'balance')

10

Methods

Bound methods, which couple together a function and the object on which that method will be invoked:

Object + Function = Bound Method

>>> type(Account.deposit)

<class 'function'>

>>> type(tom_account.deposit) # Method: One object before the dot and other arguments within parentheses

<class 'method'>

Except instance methods we mentioned before, we can create class method by using the @classmethod decorator or classmethod() function. Different from instance function, we use cls instead of self in class method.

classmethod() methods are bound to a class rather than an object. Class methods can be called by both class and object

@classmethod

def fun(cls, arg1, arg2, ...):

Inheritance

Inheritance is a technique for relating classes together.

- Conceptually, the new subclass inherits attributes of its base class

- The subclass may override certain inherited attributes

A class may inherit from multiple base classes in Python.

class CheckingAccount(Account):

"""A bank account that charges for withdrawals."""

withdraw_fee = 1 # new attribute

interest = 0.01 #differnt from Account

def withdraw(self, amount): #differnt from Account

return Account.withdraw(self, amount + self.withdraw_fee)

#Or

#return super().withdraw(self, amount + self.withdraw_fee)

Object-Oriented Design

Inheritance and Composition:

- Inheritance is best for representing is-a relationships

- E.g., a checking account is a specific type of account

- So, CheckingAccount inherits from Account

- Composition is best for representing has-a relationships

- E.g., a bank has a collection of bank accounts it manages

- So, A bank has a list of accounts as an attribute

repr and str

In Python, all objects produce two string representations:

repr- The

repris legible to the Python interpreter - The result of calling

repron a value is what Python prints in an interactive session.

- The

str- The str is legible to humans

- The result of calling repr on a value is what Python prints in an interactive session.

The repr function returns a Python expression (a string) that evaluates to an equal object. For most object types, eval(repr(object)) == object.

Example: CS61A Project Ants

>>> ant = HarvesterAnt(2) # `__repr__` is implemented in Ant class

>>> repr(ant)

'HarvesterAnt(2, None)'

>>> repr(gamestate.places["tunnel_0_0"]) # `__repr__` is not implemented in GameState class

'<ants.Place object at 0x000001F73F435B50>'

>>> print(gamestate.places["tunnel_0_0"]) # `__str__` is implemented in GameState class

tunnel_0_0

__repr__ and __str__

__repr__ goal is to be unambiguous

__str__ goal is to be readable.

There is a saying: Almost every object you implement should have a functional __repr__ that’s usable for understanding the object; while implementing __str__ is optional: do that if you need a “pretty print” functionality.

Classes that implement __repr__ and __str__ methods that return Python-interpretable and

human-readable strings implement an interface for producing string representations.

- Message passing:

- Objects interact by looking up attributes on each other (passing messages)

- The attribute look-up rules allow different data types to respond to the same message

- A shared message (attribute name) that elicits similar behavior from different object

classes is a powerful method of abstraction

- An interface is a set of shared messages, along with a specification of what they mean

Polyphonic functions

Polymorphic function: A function that applies to many (poly) different forms (morph) of data

str and repr are both polymorphic; they apply to any object.

repr invokes a zero-argument method __repr__ on its argument, str invokes a zero-argument method __str__ on its argument. If no __str__ attribute is found, uses repr string(By the way, str is a class, not a function)

How repr and str are implemented:

def repr(x):

return type(x).__repr__(x)

def str(x):

tmp = type(x)

if hasattr(tmp, '__str__'):

return tmp.__str__(x)

else:

return repr(x)

The implementation of repr makes it more clear why “when implementing str and repr, an instance attribute called __repr__ or __str__is ignored! Only class attributes are found”.

Examples

Now see some examples:

Example 1:

We can see that “If no __str__ attribute is found, uses repr string”.

class Bear():

def __repr__(self):

return 'Bear()'

>>> x = Bear()

# repr and __repr__

>>> x

Bear()

>>> repr(x)

'Bear()'

>>> x.__repr__()

'Bear()'

>>> print(x)

Bear()

>>> str(x)

'Bear()'

# str and __str__

>>> x.__str__()

'Bear()'

Example 2:

class Bear():

def __repr__(self):

return 'Bear()'

def __str__(self):

return 'a bear'

>>> x = Bear()

# str and __str__ are different from __repr__ now

>>> print(x)

a bear

>>> str(x)

'a bear'

>>> x.__str__()

'a bear'

Example 3:

We can see that “when implementing str and repr, an instance attribute called __repr__ or __str__is ignored! Only class attributes are found”. What about there is no defined class attribute __repr__ or __str__ in our class? __repr__ and __str__ are built-in for all objects in python, remember? See this in example 4.

But when you call __repr__ or __str__ through an instance, you can still find instance attribute version of __repr__ or __str__.

class Bear():

def __init__(self):

self.__repr__ = lambda: "BadBear()"

self.__str__ = lambda: "a bad bear"

def __repr__(self):

return 'Bear()'

def __str__(self):

return 'a bear'

>>> x = Bear()

# about repr and __repr__

>>> x

Bear()

>>> repr(x)

'Bear()'

>>> x.__repr__()

'BadBear()'

>>> Bear.__repr__(x)

'Bear()'

# about str and __str__

>>> print(x)

a bear

>>> str(x)

'a bear'

>>> x.__str__()

'a bad bear'

Example 4:

class Bear():

def __init__(self):

self.__repr__ = lambda: "BadBear()"

self.__str__ = lambda: "a bad bear"

>>> x = Bear()

# repr and __repr__

>>> x

<tmp.Bear object at 0x0000027C10DA1EE0>

>>> repr(x)

'<tmp.Bear object at 0x0000027C10DA1EE0>'

>>> x.__repr__()

'BadBear()'

# str and __str__

>>> print(x)

<tmp.Bear object at 0x0000027C10DA1EE0>

>>> str(x)

'<tmp.Bear object at 0x0000027C10DA1EE0>'

>>> x.__str__()

'a bad bear'

Other special Method Names in Python

Except __repr__ and __str__, there are also many special method names starting and ending with __ in Python. They are build-in behaviors.

For example:

__init__, Method invoked automatically when an object is constructed__add__, Method invoked to add one object to another__bool__, Method invoked to convert an object to True or False__float__, Method invoked to convert an object to a float (real number)__bytes__, Method invoked to compute a byte-string representation of an object__del__, Method invoked to destroy an instance. This is also called a finalizer or (improperly) a destructor. If a base class has a__del__method, the derived class’s__del__method, if any, must explicitly call it to ensure proper deletion of the base class part of the instance.

>>> x = 0

>>> bytes(x)

b''

>>> x= 4

>>> bytes(x)

b'\x00\x00\x00\x00'

Linked Lists

Implement:

class Link:

"""A linked list.

>>> s = Link(1)

>>> s.first

1

>>> s.rest is Link.empty

True

>>> s = Link(2, Link(3, Link(4)))

>>> s.first = 5

>>> s.rest.first = 6

>>> s.rest.rest = Link.empty

>>> s # Displays the contents of repr(s)

Link(5, Link(6))

>>> s.rest = Link(7, Link(Link(8, Link(9))))

>>> s

Link(5, Link(7, Link(Link(8, Link(9)))))

>>> print(s) # Prints str(s)

<5 7 <8 9>>

"""

empty = ()

def __init__(self, first, rest=empty):

assert rest is Link.empty or isinstance(rest, Link)

self.first = first

self.rest = rest

def __repr__(self):

if self.rest is not Link.empty:

rest_repr = ', ' + repr(self.rest)

else:

rest_repr = ''

return 'Link(' + repr(self.first) + rest_repr + ')'

def __str__(self):

string = '<'

while self.rest is not Link.empty:

string += str(self.first) + ' '

self = self.rest

return string + str(self.first) + '>'

Efficiency

Consider the Fibonacci problem, if we use recursive function to solve it, let’s see how many recursion it will call to get fib(n).

def count(f):

"""Count how many times the recursive function runs"""

def counted(n):

counted.call_count += 1

return f(n)

counted.call_count = 0

return counted

@count

def fib(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

else:

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1)

>>> fib(5)

5

>>> fib.call_count

15

Memorization

We can use cache to store the result during recursion, so we can get the result from cache directly if it’s already calculated instead of repeat same calculation multiple times.

def memo(f):

cache = {}

def memorized(n):

if n not in cache:

cache[n] = f(n)

return cache[n]

return memorized

@count

@memo

def fib(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return n

else:

return fib(n-2) + fib(n-1)

>>> fib(5)

5

>>> fib.call_count

9

Time complexity

Linear complexity vs Logarithmic complexity

How to distinguish between Logarithmic time complexity and Linear time complexity?

Ask yourself, what would happen to the problem size if we double the input size?

- Linear time: Doubling the input doubles the time

- Logarithmic time: Doubling the input increases the time by one step

Quadratic complexity vs Exponential complexity

Functions that process all pairs of values in a sequence of length n take quadratic time(for i in range(n): for j in range(m): ...).

Time complexity of recursive functions

Tree-recursive functions can take exponential time, like recursive Fibonacci.

Exceptions

Python exceptions are raised with a raise statement

raise <expression>.

<expression> must evaluate to a subclass of BaseException or an instance of one. Exceptions are constructed like any other object. E.g., TypeError('Bad argument!')

TypeError– A function was passed the wrong number/type of argumentNameError– A name wasn’t foundKeyError– A key wasn’t found in a dictionaryRecursionError– Too many recursive calls