Git a distributed version control system as opposed to a centralized version control system. This means that every developer’s computer stores the entire history (including all old versions) of the entire project! This is rather unlike tools like Dropbox, where old versions are stored on a remote server owned by someone else.

So what is version control system?

Version control systems (VCSs) are tools used to track changes to source code (or other collections of files and folders). As the name implies, these tools help maintain a history of changes; furthermore, they facilitate collaboration. VCSs track changes to a folder and its contents in a series of snapshots with associated messages, where each snapshot encapsulates the entire state of files/folders within a top-level directory.

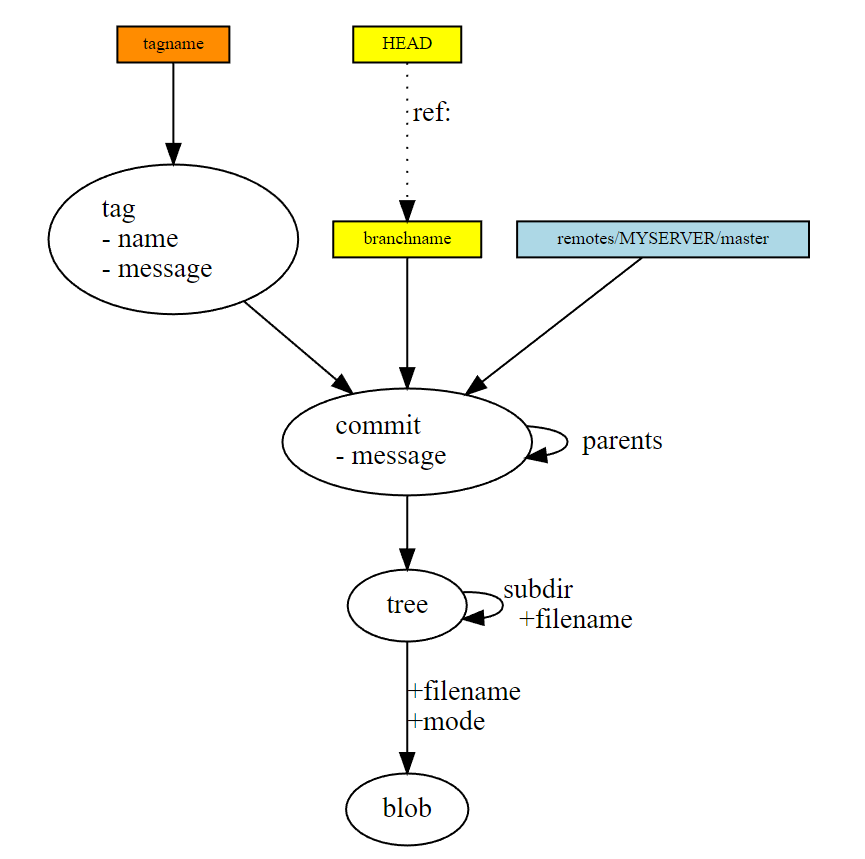

Git’s data model

Git terminology

- a file is called a “blob”. And a blob is just a bunch of bytes.

- a directory is called a “tree”, and it maps names to blobs(filename, access mode, etc is all stored in the tree) or other trees.

- a commit refers to a tree that represents the state of the files at the time of the commit. The body of the commit object is the commit message.

- a reference, or head or branch, is like post-it note slapped on a node in the DAG. They don’t get stored in the history, and they aren’t directly transferred between repositories. They act as sort of bookmarks, “I’m working here”.

- a remote reference is different to normal refs because they are in different namespace, and remote refs are essentially controlled by the remote server.

- a tag is both a node in the DAG and a post-it note (of yet another color). A tag points to a commit, and includes an optional message and a GPG signature.

snapshots

Git models the history of a collection of files and folders within some top-level directory as a series of snapshots. a snapshot is the top-level tree that is being tracked. For example, we might have a tree as follows:

<root> (tree)

|

+- foo (tree)

| |

| + bar.txt (blob, contents = "hello world")

|

+- baz.txt (blob, contents = "git is wonderful")

The top-level tree contains two elements, a tree “foo” (that itself contains one element, a blob “bar.txt”), and a blob “baz.txt”.

Modeling history: relating snapshots

Git uses a directed acyclic graph(DAG) model, instead of a simple linear history model which manages snapshots in time order. In the example below, after the third commit, the history branches into two separate branches. What does this mean? This means you and your colleague now can work independently on the project in parallel. After this, you and your colleague independently committed your work, and then decided to merged theses two branches and created a new snapshot that incorporates both parts.

Some rules we can see:

orepresents an individual commit(snapshot)- The arrows point to the parents of each commit. It’s a “comes before” relation, not “comes after”.

- Each commit(snapshot) in Git can refer to a set of parents, the commits that preceded it.(so it’s definitely not a linear history model)

- More than one parent means the commit is a merge, no parents means it is an initial commit, and interestingly there can be more than one initial commit; this usually means two separate projects merged.

- Commits in Git are immutable. So “edits” to the commit history are actually creating entirely new commits, and references are updated to point to the new ones.

o <-- o <-- o <-- o <---- o

^ /

\ v

--- o <-- o

Some situations you probably will meet during work:

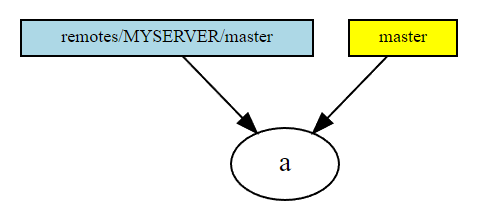

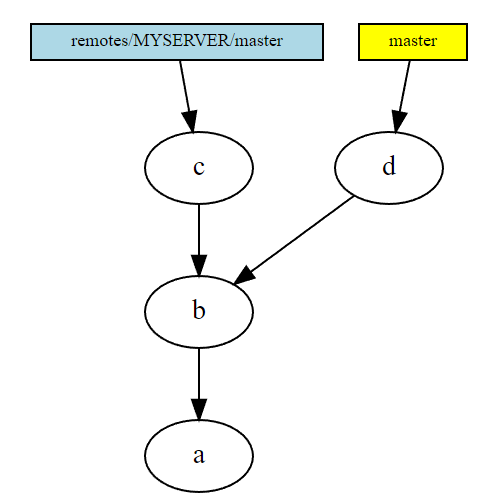

- you

cloned a remote repository with one commit in it.

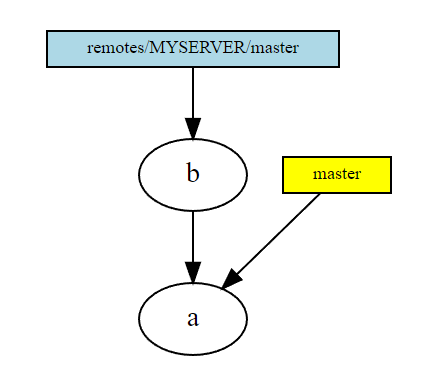

- you

fetched the remote and received one new commit from the remote, but have not merged it yet.

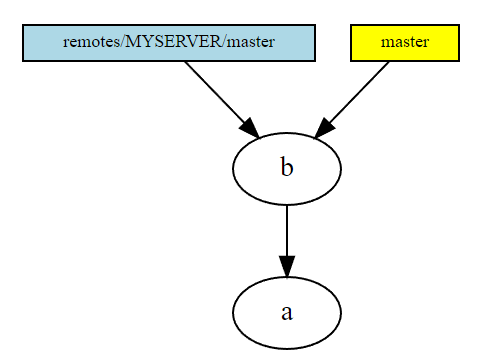

- The situation after

git merge remotes/MYSERVER/master. As the merge was afast forward(that is, we had no new commits in our local branch), the only thing that happened was moving our post-it note and changing the files in our working directory respectively.

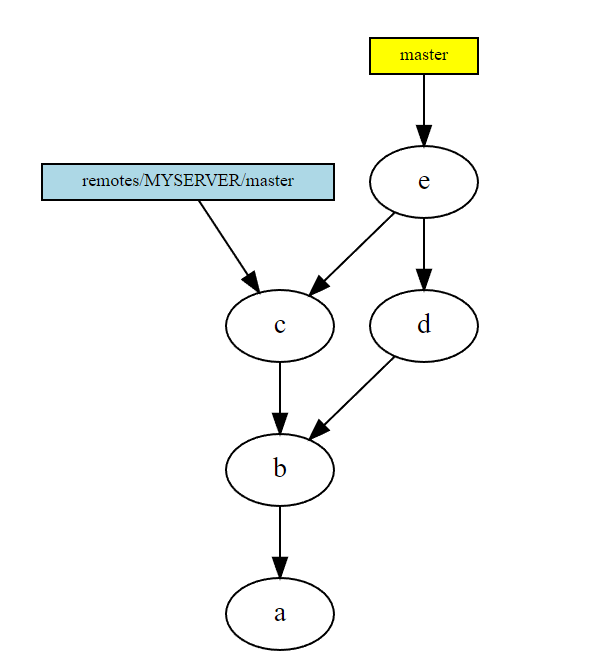

- One local

git commitand agit fetchlater. We have both a new local commit and a new remote commit.

- Results of

git merge remotes/MYSERVER/master. Because we had new local commits, this wasn’t afast forward, but an actual new commit node was created in the DAG. Note how it has two parent commits.

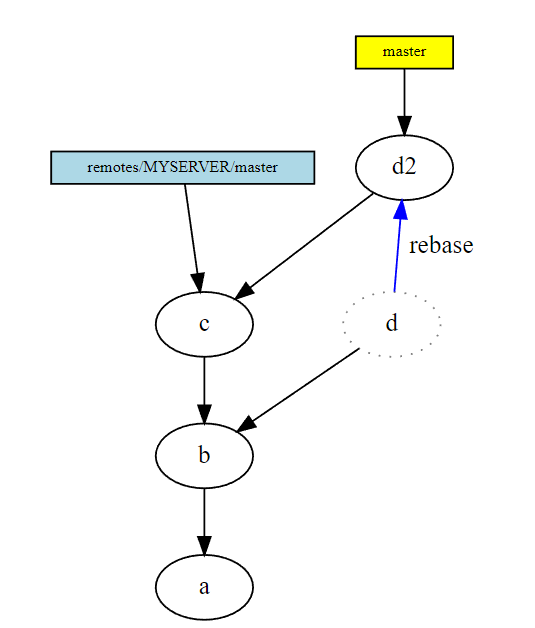

- If you have not yet published your branch, or have clearly communicated that others should not base their work on it, you have an alternative. You can rebase your branch, where instead of merging, your commit is replaced by another commit with a different parent, and your branch is moved there.

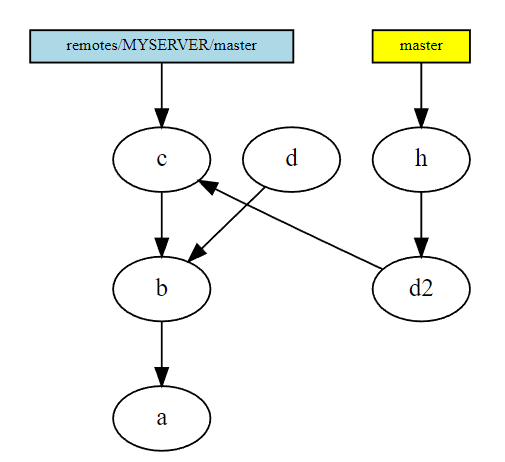

- Your old commit(s) will remain in the DAG until garbage collected. It’s good to know there’s a way out if you screwed up totally. If you have extra post-its pointing to your old commit, they will remain pointing to it, and keep your old commit alive indefinitely. That can be fairly confusing, though.

- Don’t rebase branches that others have created new commits on top of. It is possible to recover from that, it’s not hard, but the extra work needed can be frustrating.

- The situation after garbage collecting (or just ignoring the unreachable commit), and creating a new commit on top of your rebased branch.

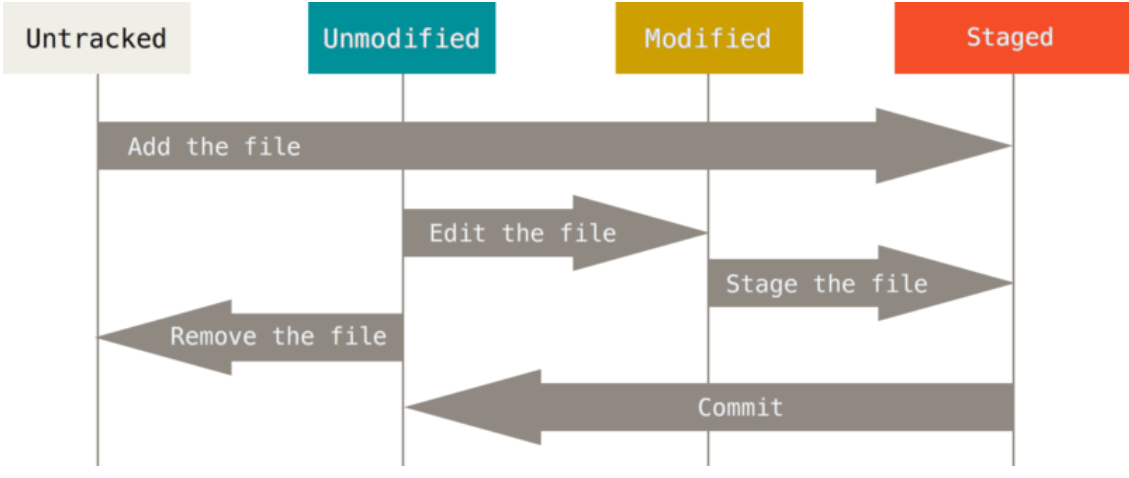

Tracked vs. Untracked Files

Using git status to check whether the file is tracked or untracked.

-

untracked files: These files have either never been tracked or were removed from tracking. Git is not maintaining history for these files.

-

tracked files: These files have been added to the Git repository and can be in various stages of modification: unmodified, modified, or staged.

- An unmodified file is one that has had no new changes since the last version of the files was added to the Git repo.

- A modified file is one that is different from the last one Git has saved.

- A staged file is one that a user has designated as part of a future commit (usually through use of the

git addcommand).

Data model, as pseudocode

General:

// a file is a bunch of bytes

type blob = array<byte>

// a directory contains named files and directories

type tree = map<string, tree | blob>

// a commit has parents, metadata, and the top-level tree

type commit = struct {

parents: array<commit>

author: string

message: string

snapshot: tree

}

Objects and content-addressing

An “object” is a blob, tree or commit as we defined above.

type object = blob | tree | commit

In Git data store, all objects are content-addressed by their SHA-1 hash(isn’t the SHA-1 of the contents of the file they represent, but of their representation in git).

Blobs, trees, and commits are unified in this way: they are all objects. When they reference other objects, they don’t actually contain them in their on-disk representation, but have a reference to them by their hash.

When a node(blobs or trees or commits) points to another node in the DAG, it depends on the other node: it cannot exist without it. Nodes that nothing points to can be garbage collected with git gc, or rescued much like filesystem inodes with no filenames pointing to them with git fsck --lost-found.

objects = map<string, object

def store(object):

id = sha1(object)

objects[id] = object

def load(id);

return objects[id]

Assume 91429bcd9a1cba27d440b3ce0565e7112730f848 is the hash code of a tree, we can use git cat-file -p 91429bcd9a1cba27d440b3ce0565e7112730f848 to see this tree, for example, it looks like this:

100644 blob c6bf99a9b8863aaae16a928416fbc9463d5ff336 a.txt

100644 blob d4a2cbedcbfcd77c6cf5db5e6a11ac907b137523 b.txt

040000 tree bd9de811df7570fd14e94747c315f73f64ae63da cafe

We can see that, this tree(master branch) itself contains pointers to its contents, two blobs(files) and one tree(directory).

While blobs are not pointers, so if you try git cat-file -p c6bf99a9b8863aaae16a928416fbc9463d5ff336, you will get the content of a.txt like:

dish name: a

how to cook: fry

taste: sour

Reference

All snapshots(commits) can be identified by their SHA-1 hashes. But this code is inconvenient to remember, so we can use references(such as master), which are pointers to commits. You can check all references by find .git/refs, and you’ll get(side is a sub-branch):

.git/refs

.git/refs/heads

.git/refs/heads/master

.git/refs/heads/side

.git/refs/tags

Pseudocode:

references = map<string, string>

def update_reference(name, id):

references[name] = id

def read_reference(name):

return references[name]

def load_reference(name_or_id):

if name_or_id in references:

return load(references[name_or_id])

else:

return load(name_or_id)

Unlike objects, which are immutable, references are mutable (can be updated to point to a new commit).

Everytime you commit changes in the master branch, master reference will be changed. That’s because master is a reference which always points to the latest commit in the main branch.

If you want to know “where we currently are” and “what the repo currently looks like”, there is a special reference called “HEAD”. The HEAD ref is special because it actually points to another ref. It is a pointer to the currently active branch.

- If you

check outa branch,HEADsymbolically refers to that branch, indicating that the branch name should be updated after the next commit operation. - If you

check outa specific commit,HEADrefers to that commit only. This is referred to as a detached HEAD, and occurs, for example, if you check out a tag name.

You aren’t encouraged to directly edit the reference files; instead, Git provides the safer command git update-ref to do this, for example, if you want to update a reference:

git update-ref refs/heads/master 1a410efbd13591db07496601ebc7a059dd55cfe9

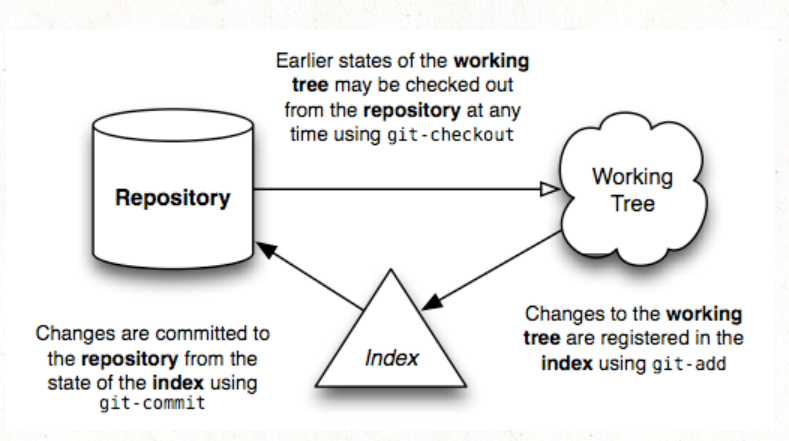

Repositories

Finally, we can define what (roughly) is a Git repository: it is the data objects and references.

A repository is a collection of commits, each of which is an archive of what the project’s working tree looked like at a past date, whether on your machine or someone else’s.

On disk, all Git stores are objects and references: that’s all there is to Git’s data model.

All git commands map to some manipulation of the commit DAG by adding objects and adding/updating references.

Staging area

Git allows you to specify which modifications now in your directory you want to include to the next snapshot when creating a commit through a mechanism called “staging area”(some also call it as “the index”).

For example, you modified both a.txt and b.txt and added them to stage area by git add .. Now both modifications are in the stage area like:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: a.txt

modified: b.txt

You don’t have to commit both of them as the next snapshot. If you want to only commit the modification of a.txt, using git commit. Then the modification of a.txt` has been included into the next snapshot and a new commit was created.

$ git commit a.txt -m "only commit a.txt"

[master 3560557] only commit a.txt

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

Now check the stage area:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: b.txt

Git command-line interface

Basics

| command lines | descriptions | examples |

|---|---|---|

git help <command> or git <command> --help |

The former will automatically open a mannual webpage for you. The latter will show command usages in the interface. Note that the latter is internally converted into the latter, so they are identical. | git help log or git log --help |

git init |

creates a new git repo, with data stored in the .git directory |

git init myProject |

git status |

tells you what’s going on | |

git add <filename> |

adds files to staging area | |

git commit |

creates a new commit | git commit -m "init" or git init -m "only modify a.txt. How to write commit file: link git commit --amend -c HEAD means you want to modify the commit message file for commit HEAD points to or add forgotton files to this commit. |

git log |

shows a flattened log of history | git log a.txt shows history of file a.txt. git log --all --graph --decorate visualizes history as a DAG. |

git diff |

git diff git diff `git diff 64f879533ecded5c2312637752dcf7eb92ade234 b.txt` will show you the differences in file b.txt between the current snapshot and the snapshot you're interested in(with sha-1 code "64f879533ecded5c2312637752dcf7eb92ade234". |

|

gitk |

a GUI prompted by the command line | |

git reset HEAD [file] |

Unstage a file that you haven’t yet committed. Let’s say you accidentally started tracking a file that you didn’t want to track. (an embarrassing video of yourself, for instance.) Or you were made some changes to a file that you thought you would commit but no longer want to commit quite yet. | |

Remote repository

| command lines | descriptions | examples |

| — |————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-|———-|

| git clone [remote-repo-URL] | Makes a copy of the specified repository, but on your local computer. Also creates a working directory that has files arranged exactly like the most recent snapshot in the download repository. Also records the URL of the remote repository for subsequent network data transfers, and gives it the special remote-repo-name “origin”. | |

| git remote add [remote-repo-name] [remote-repo-URL] | Records a new location for network data transfers | |

| git remote rename [old-name] [new-name]| rename your remote | |

| git remote rm [remote-name] | remove a remote | |

| git remote -v | list all the remotes you have | |

| git remote -v | Lists all locations for network data transfers | |

| git pull [remote-repo-name] master | Get the most recent copy of the files as seen in remote-repo-name. This is equivalent to a fetch + merge. | |

|git fetch [remote-name] | This is analogous to downloading the commits. It does not incorporate them into your own code. our partner may have created some changes that you’d like to review but keep separate from your own code. Fetching the changes will only update your local copy of the remote code but not merge the changes into your own code. | |

| git push [remote-repo-name] master | Pushes the most recent copy of your files to the remote-repo-name | |

Branching and merging

| command lines | descriptions | examples |

| — |———————————————————————————————————————| — |

| git branch [new-branch-name] | create a branch off of your current branch | |

| git checkout <revision> | updates HEAD and current branch | git checkout anotherBranch or git checkout oldCommit(this will be a detached HEAD) |

| git branch -d [branch-to-delete] | delete branches | |

| git branch -v | figure out which branch you are on with this command. The -v flag will list the last commit on each branch as well. | |

Exercises from Missing Semester Course

- Clone the missing-semester repository from Github.

- Explore the version history by visualizing it as a graph. ===>

git log --all --graph --decorate - Who was the last person to modify README.md? (Hint: use

git logwith an argument). ===>git log README.md - What was the commit message associated with the last modification to the

collections:line of_config.yml? (Hint: usegit blameandgit show). ===>git blame _config.yml, get SHA-1 codea88b4eacforcollections:line, thengit show a88b4eac

- Explore the version history by visualizing it as a graph. ===>

- One common mistake when learning Git is to commit large files that should not be managed by Git or adding sensitive information. Try adding a file to a repository, making some commits and then deleting that file from history (you may want to look at this).

- Clone some repository from GitHub, and modify one of its existing files. What happens when you do git stash? What do you see when running git log –all –oneline? Run git stash pop to undo what you did with git stash. In what scenario might this be useful?

- Like many command line tools, Git provides a configuration file (or dotfile) called ~/.gitconfig. Create an alias in ~/.gitconfig so that when you run git graph, you get the output of git log –all –graph –decorate –oneline. Information about git aliases can be found here.

- You can define global ignore patterns in ~/.gitignore_global after running git config –global core.excludesfile ~/.gitignore_global. Do this, and set up your global gitignore file to ignore OS-specific or editor-specific temporary files, like .DS_Store.

- Fork the repository for the class website, find a typo or some other improvement you can make, and submit a pull request on GitHub (you may want to look at this).